The -7 C degree start was a sharp reminder that while our night had been spent shuttling between our vehicle, lightweight sleeping bags and the warmth of the humanitarian tent with its wood-burning stove, there were hundreds of thousands of Ukrainian civilians only just surviving in atrocious conditions less than seven short hours’ drive away in Mariupol and other beleaguered locations subject to the Russian onslaught.

Ahead, the four hour run into Odesa to meet maritime stakeholders started with the knowledge that between the border and our meeting location was a stretch of road with many unknowns, rolling go/no go decision points and martial law conditions.

Despite best efforts to garner local knowledge, check updates with intermittent data signals and confirm access to live to report, even the limited numbers of petrol stations left open had subdued staff who understandably limited their engagement with strangers despite our best efforts to share a smile, comical moment or a thumbs-up.

![David Hammond and Evgeniy Sukachev of Black Sea Law Co on C7 News Ukraine[1]](https://themarinelearners.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/David-Hammond-and-Evgeniy-Sukachev-of-Black-Sea-Law-Co-on-C7-News-Ukraine1.jpg)

![David Hammond and Evgeniy Sukachev of Black Sea Law Co on C7 News Ukraine[1]](https://themarinelearners.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/David-Hammond-and-Evgeniy-Sukachev-of-Black-Sea-Law-Co-on-C7-News-Ukraine1.jpg)

Numerous checkpoints, dug-in positions, armoured vehicles, and mined areas were dispersed between towns and villages that were seemingly deserted with no visible people, cars or life, while numerous stray or abandoned dogs roamed freely. The pattern of life had changed.

Our route had little traffic coming or going until we approached the outskirts of Odesa, and where checkpoints increased in frequency, questioning became more detailed and comprehensive vehicle searches were the norm. This was reassuring. It was professional, and it was focused.

Passing along the impressive Black Sea coast, the sandy beaches and holiday complexes that had held the promise of a vibrant past life had the clear potential to do the same once again. Nonetheless, at the time of writing, Russian naval bombardment continued into the locality, which was virtually deserted except for occasional bars, food shops and the stark contrast of a patisserie which appeared more in keeping with a Paris street than a war zone under military control.

The port complexes are densely covered with buildings, warehouses, cranes and bunkering facilities. Bombardment here would leave little infrastructure working afterwards and create an even greater humanitarian catastrophe. Attacking such locations with an intent to destroy them would appear to make no rational sense, and as civilian infrastructure, it is against International Humanitarian Law.

A late morning arrival at the offices of our principal contact was a return to apparent normality in a city which was alive but noticeably quiet on the historic streets with few people out, but a reassuringly high level of internal security presence.

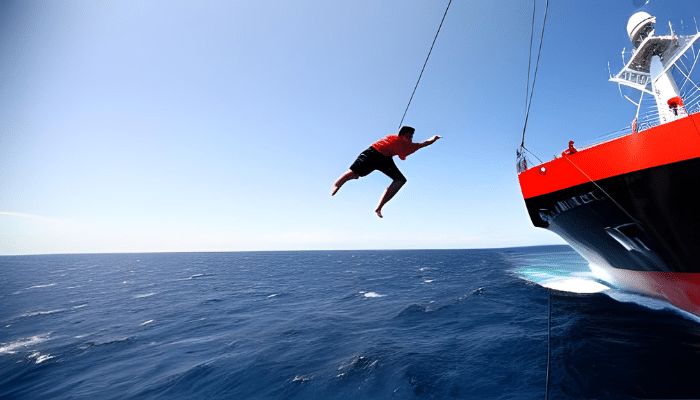

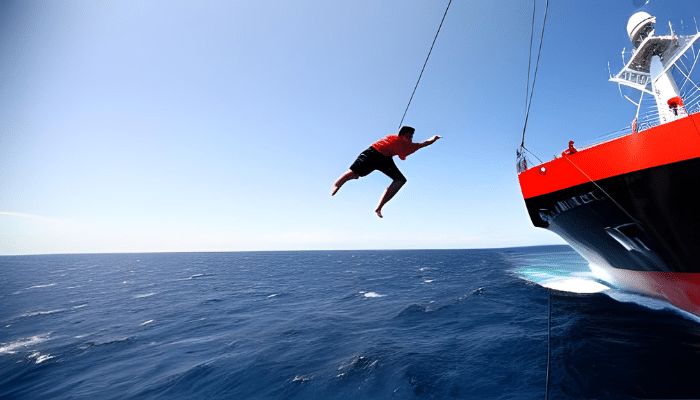

In an effort to maintain flexibility and mobility, we had successive meetings with a major ship manager and a senior union official. We undertook an interview with the local television station to explain our presence and support for investigating potential war crimes and human rights abuses towards seafarers, maritime workers, and their families.

Nonetheless, there was an understandable and palpable air of edginess, suspicion, and plenty of questions to establish who you were and then to check and re-check. There was also an all-pervading air of resistance, anger and focus that Odesa simply would not fall.

Garnering the inside detail of the situation for seafarers confirmed earlier international reporting that in excess of 100 ships were affected though what was more alarming was the estimated (as yet unconfirmed) figure of around 1500 seafarers effectively still in the line of fire, some experiencing challenging onboard conditions and otherwise not able to be extracted.

While periodic Russian naval bombardment was currently to the south, air attacks had been ongoing around the port area through Ukraine air defences had held their own, with some seafarers being squarely within the area of impact.

The common thread of discussion was one of a speedy return to normal life interspersed with hope, rather than any resignation to loss of identity of the country.

Individual concerns centred on the future for Ukrainian ports, trade exports, wider food security and seafarers’ futures as manning agencies and managers may move away from using the estimated 200,000 workforce, thereby depriving the state of much-needed income, seafarers’ futures, and security for their families.

Some of those we spoke to affirmed their commitment to laying down their lives to protect their homeland, homes, and families. It was a level of personal commitment, national affirmation, and sincerity that one rarely experiences first-hand. It was a privilege to have been around such persons and such courage.

Reference: humanrightsatsea.org

We believe that knowledge is power, and we’re committed to empowering our readers with the information and resources they need to succeed in the merchant navy industry.

Whether you’re looking for advice on career planning, news and analysis, or just want to connect with other aspiring merchant navy applicants, The Marine Learners is the place to be.