Seafaring is a rewarding and important career choice for 1.6 million workers globally, but for many years the plight of a seafarer has been kept in the dark as being a profession that is out of sight and out of mind, especially to the general public.

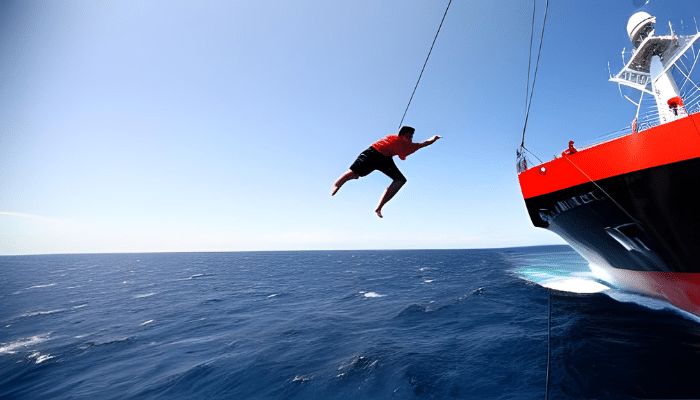

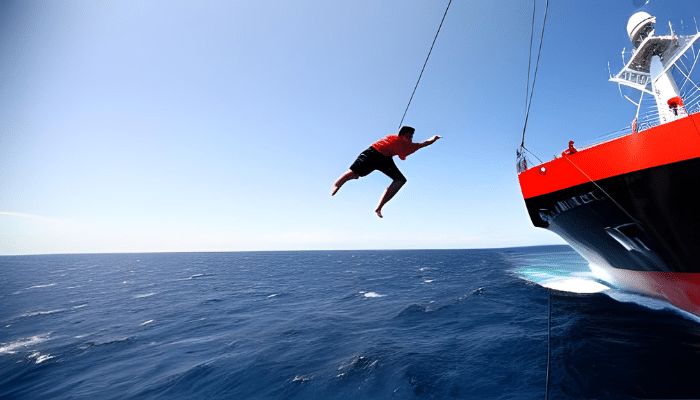

Seafarers can spend many months at sea, sometimes well in excess of their contracts, facing some of the harshest and most treacherous working conditions of any workforce. Life onboard can also be challenging; being away from family and friends for long periods with limited means to make contact, feeling isolated and lonely whilst working long hours and sometimes getting little rest. This was significantly exacerbated during the height of the COVID pandemic and the associated international crew-change crisis.

Reports of bullying and harassment are not unheard of, and life at sea means there is no escape from the vessel they are working on. It has been well-documented that seafarers are ranked among one of the highest occupational groups for having a significant risk of work-related stress, and depression is a well-known factor that impacts mental health, including the tragedy of suicide at sea.

In July 2022, the UK Department for Transport for London and contributions from Human Rights at Sea and other key industry stakeholders published research and shed much-needed light on the hidden mental health crisis affecting seafarers.

The report explicitly highlights suicide at sea and demonstrates a clear acceptance by the maritime sector that suicide is under-reported. Reasons for this include difficulty defining if death is a suicide or not – working at sea is dangerous and accidental deaths are not unusual, so determining if a death is accidental or suicide can be complex, especially without policing or forensic support onboard.

Recently, Advisory Board member Professor Neil Greenberg and Dr Samantha K Brooks published their review on learnings from the Covid-19 pandemic to prepare and better support the mental health of seafarers. It goes some way to understanding how best to support seafarers in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic and any other crisis that may arise.

The stigma that surrounds suicide often means that families may want to be protected socially as well as financially due to contract clauses that may have an impact when their loved one dies. Even when support is accessible, the embarrassment surrounding mental health makes it often difficult for seafarers to come forward and seek help.

The 2022 UK report is a significant step in the right direction for greater awareness and is a welcome start, but we must keep talking.

Moving forward, there needs to be a unified international approach to increasingly safeguard our seafarers’ mental health and break the stigma.

One suicide will always be one too many.

Reference; Human Rights At Sea

We believe that knowledge is power, and we’re committed to empowering our readers with the information and resources they need to succeed in the merchant navy industry.

Whether you’re looking for advice on career planning, news and analysis, or just want to connect with other aspiring merchant navy applicants, The Marine Learners is the place to be.