In calm seas, a vessel was stopped while underway to allow the crew to undertake boat drills. While the lifeboats were tested, the rescue boat was launched and manoeuvred close to the ship by a three-person crew. The rescue boat trials lasted for about an hour before the crew brought the boat alongside for recovery.

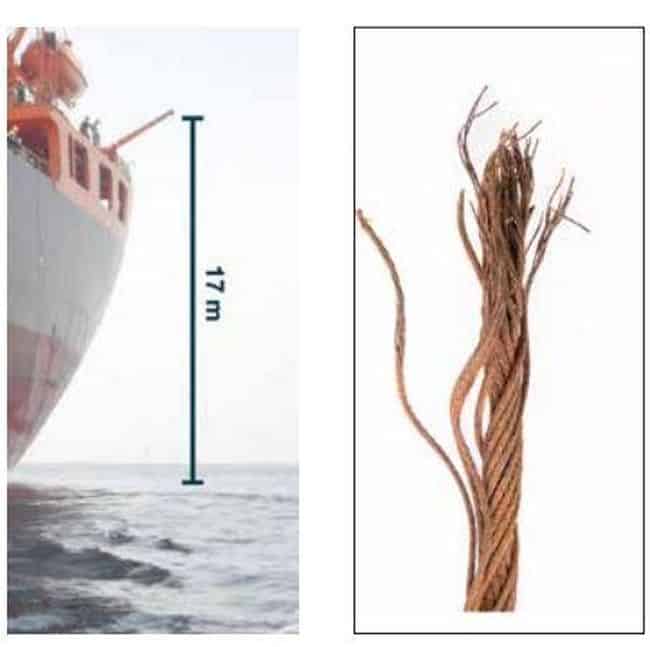

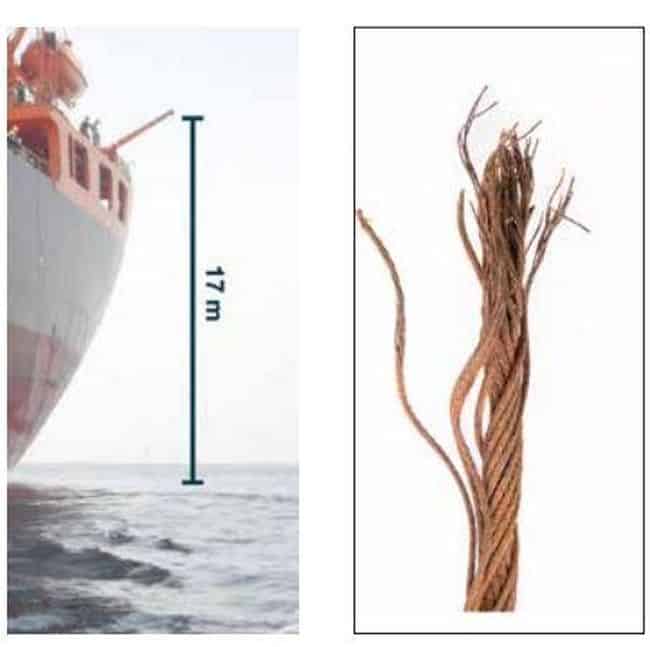

Once the hook and painter line was fastened, the crew in the boat sat on the floor in a stable manner and the hoist was started. When the boat reached the boat deck, the winch was stopped. Suddenly, the wire failed and the boat fell 17 metres, hitting the water upright.

The engine was torn off its foundation, the bottom hull cracked, and the boat slowly drifted alongside the ship’s port side. All three crew members were still in the boat but seriously injured. The alarm was immediately raised.

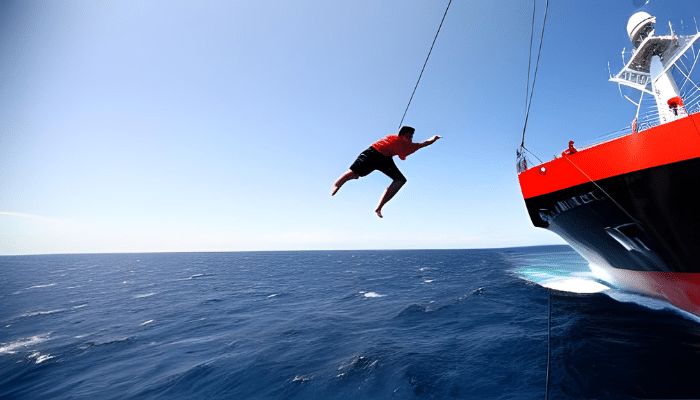

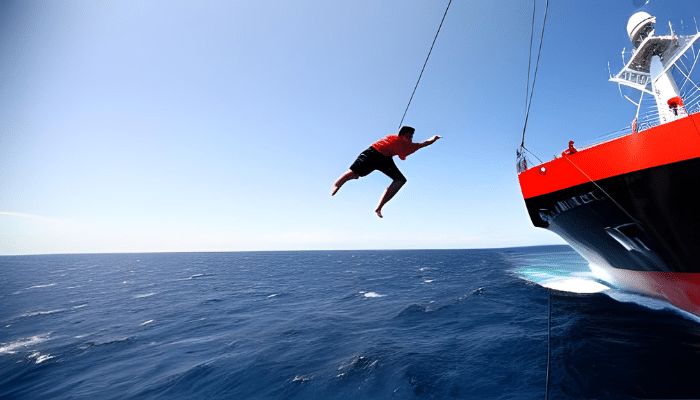

It was quickly decided that the best option was to use the main deck crane to hoist the boat back on board with the crew inside. It seemed that the only option was to have a crewmember jump into the sea and swim to the rescue boat to retrieve the painter line, which had been lost overboard when the wire broke.

One crewmember volunteered to don a life jacket, climb down the combination ladder and swim to the boat. Once the painter line had been retrieved, the crew on the deck pulled the boat forward below the deck crane. The volunteer swimmer had climbed into the boat ready to fasten the deck crane hook to the boat.

After the hook had been fastened, he swam back to the combination ladder and climbed up on deck. Approximately 20 minutes after the boat fell into the sea, it was hoisted up to the main deck. The injured crew members were assessed and given first aid. One victim needed immediate treatment and was taken to the ship’s hospital. The next morning the vessel arrived at a port anchorage where disembarkation of the injured crewmembers was arranged.

The official report found that the rescue boat davit’s wire rope parted because it was corroded to the extent that its load bearing capacity was exceeded when the rescue boat was hoisted. However, the parting of the wire rope was an ‘accident event’ which could not in itself explain why the rescue boat system failed.

Even though the company’s Planned Maintenance System (PMS) instructed the officers to inspect and maintain the wire rope, they did not act upon the deteriorating condition of the wire rope. Neither did any of the other officers who continuously inspected, maintained and operated the rescue boat system even when the wire rope was readily visible.

The reason the poor condition of the wire rope was not recognised earlier was a combination of at least three factors:

Reference: nautinst.org

We believe that knowledge is power, and we’re committed to empowering our readers with the information and resources they need to succeed in the merchant navy industry.

Whether you’re looking for advice on career planning, news and analysis, or just want to connect with other aspiring merchant navy applicants, The Marine Learners is the place to be.