A loaded VLCC was underway. The vessel’s weather routing service was forecasting waves with a significant height of more than six metres. The vessel’s speed was slowed to between five and six knots to reduce the chances of shipping seas on deck.

Due to the heavy weather restrictions, access to the main deck was not permitted except when specifically permitted by the Master. This restriction was even posted on the central notice board.

One morning, a bilge alarm sounded for the bosun stores forward. The Master, on the bridge with the OOW, assessed the weather; they observed rough seas and a long and heavy swell. Sprays were being experienced on the starboard bow, but no seas came on deck. The deck on the port side bow remained dry. The ship’s course was altered to give a better lee and the Master gave the Chief Officer and the Bosun permission to proceed forward via the safety walkway to check the bosun store bilges.

A few minutes later, the Chief Officer reported that they were inside the bosun store and they found the space dry. The bilge alarms were tested and both port and starboard alarms worked normally. The Master asked the Chief Officer to have a quick look at the anchor lashings before returning aft. A few minutes later, the Chief Officer reported that the port anchor lashing seemed to be loose; he informed the Master that he was going to tighten it.

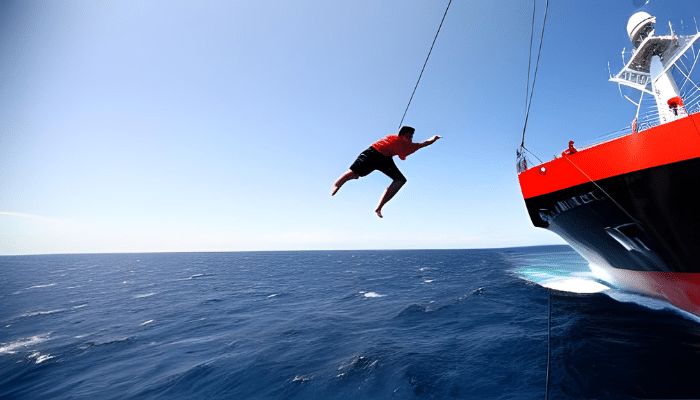

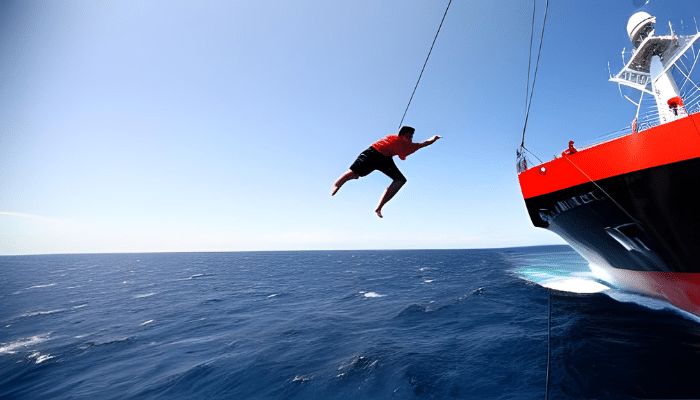

Soon after, the Master saw a wave near the bow that appeared to be somewhat larger than the others. He warned the Chief Officer by VHF radio but seconds later, huge amounts of water washed over the bulwark. Visual contact with the Bosun and the Chief Officer was lost.

The Bosun was seen lying on the walkway near the port anchor winch, but the Chief Officer was still not visible. The general alarm was sounded and an announcement was made. The vessel was slowed yet further and manoeuvred to have the waves astern, at which point a rescue team went forward. The rescue team found the Chief Officer and Bosun as indicated on the diagram and the victims were brought to the ship’s hospital.

The Chief Officer was unconscious with a deep laceration to the head. He had lost many of his teeth and his breath was accompanied by moaning. The Bosun was responsive, and he indicated that he had a serious pain in his back and his left leg and left wrist appeared broken.

Too far at sea to quickly regain a port and with bad weather preventing helicopter evacuation, a rendezvous with navy vessels was coordinated, but the meeting would take eight to ten hours. Unfortunately, during the course of the day, both victims became unresponsive and both died. Their bodies were disembarked the next day.

The investigation found that a wave, significantly higher than the observed waves, hit the vessel while the Chief Officer and the Bosun were at the bow. The investigation also found, among other things, that communication by portable satellite phone was not possible from the ship’s hospital.

Radio Medical Advice (RMA) was received by satellite phone on the bridge, but the hospital was five decks below. Immediate and critical medical treatment of the victims based on communications with RMA had to be relayed verbally from the bridge satellite phone to the caregiving personnel in the hospital either by internal phone, or in person. The report did not speculate on whether having communications directly to the ship’s hospital would have made a difference in saving lives.

Lessons learned

The Nautical Institute

We believe that knowledge is power, and we’re committed to empowering our readers with the information and resources they need to succeed in the merchant navy industry.

Whether you’re looking for advice on career planning, news and analysis, or just want to connect with other aspiring merchant navy applicants, The Marine Learners is the place to be.