There are a number of man-made canals across the world built to cut short the route of ships. Such canals, including the Panama Canal, the Suez, The White Sea-Baltic Sea and Volga-Don Canal, etc. offer easier or alternative transportation routes across major seawater networks worldwide, enabling the movement of goods or people in much more comfortable ways.

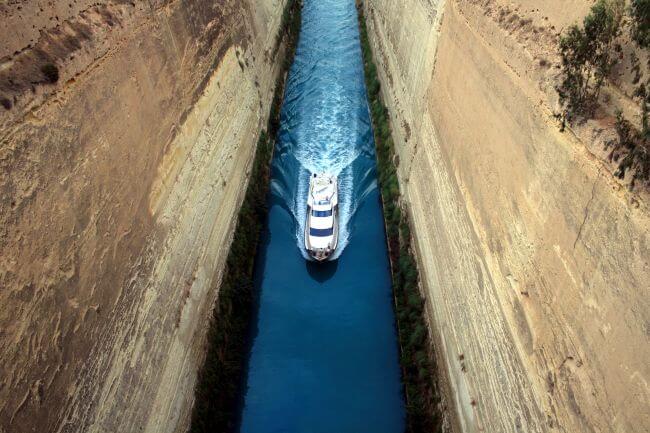

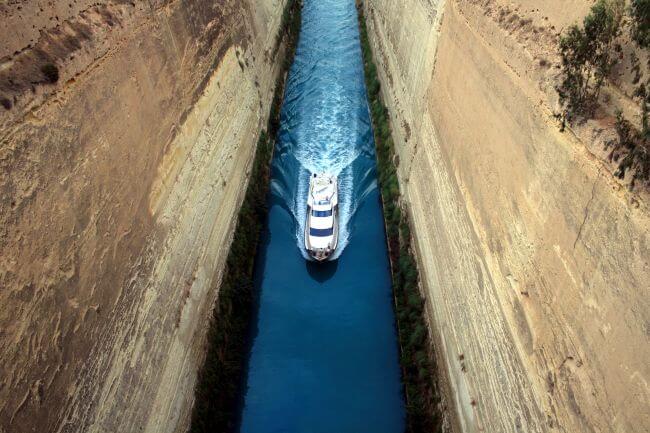

The Corinth Canal in Greece is one of the oldest such canals in the world and a very important navigational route in the Greek archipelago connecting the Gulf of Corinth with the Saronic Gulf.

The canal’s position, thereby, also separates the Peloponnese peninsula – conveniently converting it into an island – from the Greek mainland. And, while the Greece canal is quite narrow, it is a fact that the canal is a vital lifeline for ships wanting to enter the Aegean Sea.

The Corinth Canal cuts through the isthmus of Corinth in Greece, connecting the Ionian Sea with the Aegean. The canal saves around 300 miles of the journey for ships around the cape, enabling them to reach ports to the east faster and safer. Presently, it is a popular destination and the 2nd most visited place in Greece, attracting people from across the world. Corinth is an archaeological site with many ancient landmarks, such as the Apollo temple and the Acrocorinth, the Acropolis of ancient Corinth.

Spanning a distance of 6.3 kilometres, the Corinth Canal has a depth of 26 feet, and its width alters between a minimum of 69 feet and a maximum of 82 feet at the bottom and at the surface, respectively. Surrounded by walls standing at a height of 170 feet, the canal helps ships to save a journey of 185 nautical miles.

Related Reading: 10 Important Facts About Panama Canal

Before the construction of the canal, ships passing through this oceanic area had to endure a circuitous and roundabout route in order to enter the Mediterranean and the Black Seas in addition to the Aegean Sea.

The construction of this canal helped seafarers avoid the dangers of sailing around the Peloponnese’s treacherous southern capes while moving between the Gulf of Corinth and the Saronic Gulf.

However, the Corinth Canal is nowadays losing its economic importance due to its inability to accommodate modern large vessels, though many small cargo ships and cruise ships still make a voyage through the canal regularly.

In order to uphold its legacy, the local authorities are working on ambitious plans to make changes in the measures of the canal, enabling the passage of modern ocean freighters.

In terms of its construction, the Corinthian Canal is not an event that was planned to be built a few years ago, but in fact, was a dream envisioned a couple of thousands of years ago.

The suggestion for cutting through the isthmus of Corinth was started in classical times as many rulers in Greece dreamed of such a passage. The towns of Corinth and Isthmia are situated close to the west and east ends, while a highway crosses the canal and links Athens to Peloponnese.

However, it is suggested that the idea was actually conceived during the time of Periander, who was the second tyrant of Corinth in the 7th century BC. However, it was an ambitious project and not even Julius Caesar and not even the Roman Emperors Nero or Caligula could complete their plans and build a canal.

The canal was executed in the late 19th century, inaugurating on July 25, 1893.

Related Reading: A brief history of the Panama Canal

The construction of the Corinthian Canal was fraught with a lot of complications, though the concept was envisioned under the regime of Periander.

Primarily, superstition and orthodoxy, coupled with a lack of infrastructural facilities, tricky geological conditions and war, led to the procrastination of the construction of the canal.

To begin with, the route of the canal was composed of treacherous rocks along with being in a high-seismic zone. This made the route highly volatile and prone to unprecedented earthquakes. It needs to be noted that when the construction of the canal actually started in the late 1800s, a major portion of the rock formations had to be overhauled and removed before the engineers and architects could start with their work.

The plan was once abandoned after Pythia, the High Priestess of the Temple of Apollo at Delphi or at the Oracle of Delphi, warned that such a project would incur the Gods’ wrath. In addition, Apollonius of Tyana, the Greek philosopher, had prophesied that anyone who took the initiative to build a Corinthian canal would end up with illness.

However, a timeline of the emperors who tried to convert the engineering dream into reality needs to be mentioned.

Related Reading: 10 Famous Shipping Canals in The World

This timeline would help understand the happening of events in proper chronological order:

The otherwise autocratic Periander was the very first ruler to have visualised a canal to bridge the navigational distance encountered by ships. However, Periander abandoned the project due to lack of viability and as he was wary of exacting the wrath of the gods.

When the plan proved difficult, he had a limestone platform with a simpler and less costly overland portage road known as Diolkos built where the ships would be loaded till they could pass from one Gulf to another.

With this stone carriageway, the ships were rolled onto the Olkos, a wheeled contraption, which made the loading and unloading of the ships easier.

Ships whose dimensions made it impractical for them to be loaded onto the Diolkos and the Olkos, their cargo used to be removed at one shore and then re-loaded onto a waiting ship at the other shore. The procedure was complicated, though the only feasible one at that time. Even after decades, the remnants of the Diolkos can be found next to the modern Corinthian Canal.

After Periander, Demetrios Poliorkitis, Julius Caesar, Caligula and Hadrian were the other Greek rulers who tried to elaborate on the idea of building a canal between the Gulf of Corinth and the Saronic Gulf.

Dimitrios Poliorkiti, who was the King of Macedon, began excavations as part of the project in 307 BC but later abandoned the plan after he was told by his engineers that such a canal linking the Aegean and the Adriatic would flood the Aegean, as the Sea God Poseidon opposed the construction of the canal.

The Roman dictator Julius Caesar had moved his plans despite a dark prophecy from philosopher Apollonius of Tyana but was assassinated before he could begin digging the canal. Caligula, Caesar’s successor, the third Roman Emperor, went ahead with plans to construct the canal. However, he was warned by Egyptian experts who incorrectly claimed that the Corinthian Gulf was higher than the Saronic Gulf. However, similar to Caesar’s fate, he was also assassinated before starting the construction of the canal.

The emperor Nero had some success regarding the construction of the Canal of Corinth. He was the first ruler – and the first person overall – to dig the land, indicating the beginning of the canal construction. However, the lack of financial infrastructure and Nero’s assassination led to the abrupt stopping of the canal construction.

According to the historic documents, Emperor Nero had started the construction of the canal with a group of 6,000 slaves, mostly Jewish prisoners of war, smashing around 3,000 meters of rock on the Corinthian Gulf side. The workers built 130–160 feet wide trenches from both sides, and a few of them were assigned to drill deep shafts in order to understand the quality of the rock.

However, the work had to be stopped when he was forced to return to crush a rebellion before his death. Under Nero’s supervision, almost a tenth of the total distance across the isthmus was also constructed, historians suggest.

The modern canal sits on the same route that Nero started constructing.

After Nero’s era, the discussion of the canal came up in 1687, when the Venetians initiated the plan after their conquest of the Peloponnese. But the plan was abandoned when it proved to be too daunting.

In the year 1830, after the fall of the Ottoman Empire, the newly appointed Greek governor Ioannis Kapodistrias led the resurgence of the idea of the Corinth Canal. He entrusted the project to the French engineer Virle d’ Uct. But the construction had to be postponed since the new Greek government was not in a position to spend the estimated cost of 40 million gold francs.

Thus, it was in 1869 the government led by Prime Minister Thrasyvoulos Zaimis allowed Austrian private entrepreneurship owned by Etienne Tyrr – the then General of Austria, to start the construction. Though finally, the digging of the canal began in 1882; the financial crisis faced by the company when French banks refused to lend money after the company that was constructing the Panama Canal went bankrupt, resulting in a temporary pause of the construction works.

Later, the need for further capital investment was brought in by a Greek entrepreneur in the form of five million francs in the year 1890. The Greece Canal was finally built and brought into operation on October 28, 1893, after overcoming and surpassing many roadblocks.

Once opened, the canal was not economically successful as expected earlier. The difficulty of navigating through the canal and also the frequent high winds and strong currents reduced the number of passages through the canal.

The larger ships could only cross the canal with the help of tugs, and the vessels could only pass through the canal one convoy at a time on a one-way system.

Related Reading: Panama Canal Expansion Project and Its Benefits

Even now, the narrowness of the canal does not permit large vessels to pass through it. This again poses a huge problem to the viability of the Canal of Corinth in terms of the size of the contemporary vessels.

Moreover, the Corinth Canal is not without its risks.

The canal experienced earthquakes in the year 1923, which caused around 40,000 cubic metres of the wall surrounding the canal to cave into the water.

The accumulated debris took around two years to be fully cleared up, after which navigation could resume again. Even now, high-risk alerts are posted regularly to the ships using this marine navigational route. Similarly, the Corinth Canal was also damaged during World War II as it was one of the locations of strategic importance.

According to war documents, the German troops tried to capture the main bridge over the canal in 1941 when troops of Britain and Nazi Germany fought in the Battle of Greece. Despite being defended by the British, the bridge was captured by the Germans in a surprise attack.

In 1944, as German forces retreated from Greece, they used explosives in “scorched earth” operations to put the canal out of action and to hinder repair work. After a few years of restrictions, the canal was re-opened for all ship traffic by September 1948.

However, in spite of such debilitating factors, it cannot be denied that the Corinthian Canal is an engineering marvel deserving of hearty appreciation. Though remaining lesser known when compared to projects like Suez and Panama, it needs to be placed in history for the efficiency of marine engineering behind it.

Currently, according to various reports, around 15,000 ships from at least 50 countries transit through the canal. The canal mostly sees the presence of small vessels, cruise ships and yachts, as it has become one of the major tourist destinations in the country, enabling visitors to take short trips through the canal.

In a bid to accommodate modern larger ships and also to boost the country’s economy, the authorities have proposed a canal widening/expansion project in the 2013-2016 Strategic and Operational Plan of the Corinth Canal.

You might also like to read:

Disclaimer: The authors’ views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect the views of The Marine Learners. Data and charts, if used, in the article have been sourced from available information and have not been authenticated by any statutory authority. The author and The Marine Learners do not claim it to be accurate nor accept any responsibility for the same. The views constitute only the opinions and do not constitute any guidelines or recommendation on any course of action to be followed by the reader.

The article or images cannot be reproduced, copied, shared or used in any form without the permission of the author and The Marine Learners.

We believe that knowledge is power, and we’re committed to empowering our readers with the information and resources they need to succeed in the merchant navy industry.

Whether you’re looking for advice on career planning, news and analysis, or just want to connect with other aspiring merchant navy applicants, The Marine Learners is the place to be.